Franklin truly was a genius. He set an example for American ingenuity and advances in science that inspired generations of entrepreneurs and self-taught inventors.

Franklin truly was a genius. He set an example for American ingenuity and advances in science that inspired generations of entrepreneurs and self-taught inventors.

This is the latest title in the excellent series of titles from Chicago Review Press which also includes George Washington for Kids, The American Revolution for Kids, and Abraham Lincoln for Kids.

The subtitle on this volume follows the same formula as the others, “His Life and Ideas with 21 Activities.”

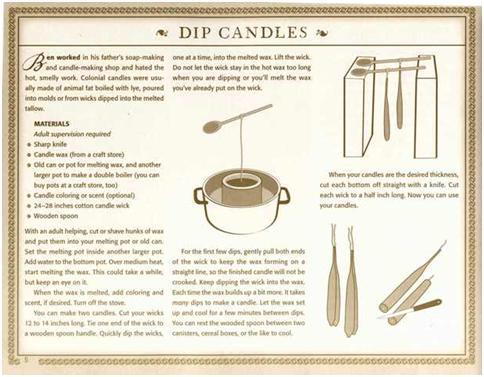

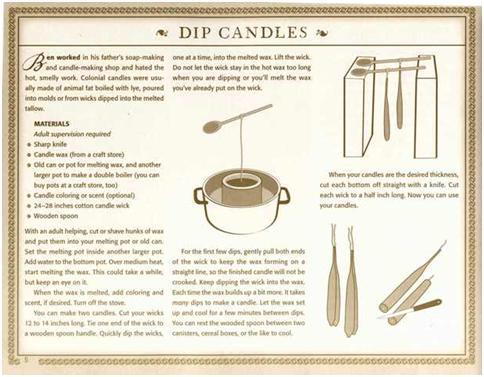

The book is, first of all, an excellent illustrated biography of Franklin – whose life is perhaps the most remarkable of all the founding fathers. Part 1 – “As a Young Genius” provides us with Franklin’s family history. His father was a Puritan, who left England in 1683 and migrated to the capital of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, Boston. Benjamin was born in 1706, the 12th of fourteen children. Ben grew up in colonial Boston. He was a bookish lad, but didn’t much like school. At ten he apprenticed to his father as a soap and candle-maker. This he apparently hated even more than school. At twelve, his father decided to apprentice Ben to one of his older half-brothers, who was a printer. Ben liked work in the print shop, but hated working for his brother. In 1723, at the age of seventeen, Ben slipped away from Boston without a word to his family or his parents. There are five activities for this section: Grow Crystal Candy; Shoot a Game of Marbles; Pour a Bar of Soap; Dip Candles; Hasty Pudding.

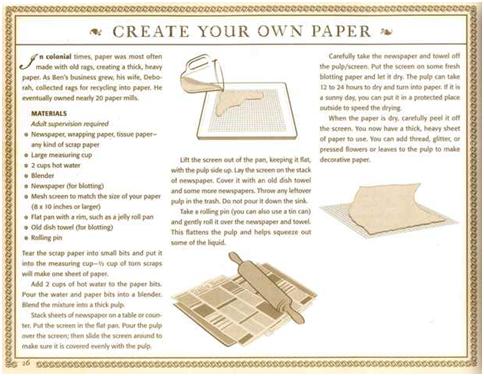

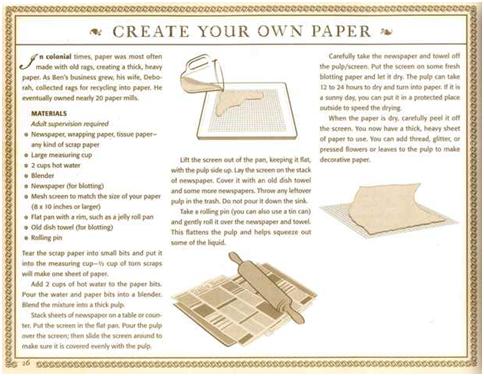

Part 2 – “A Young Man of Promising Parts” follows Ben’s move from Boston to New York and then to Philadelphia. In Philadelphia he found work in a printer’s shop, but was ambitious to establish his own business. In 1724, he sailed for London with a friend, thinking he had the backing of the Royal Governor of Pennsylvania. Sadly, the Governor had misled Ben with a promise of a letter of credit. The truth was, the Governor had no credit to lend. Ben went to work for a printer in London. In two years he had saved enough to return to Philadelphia. Back in Philadelphia, two more years of hard work finally enabled Ben to start his own business. In 1729, he published the first issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette. Most of the articles were written by Ben. There are three activities for his section: Create Your Own Paper; Make a Leather Apron; Start a Junto.

Part 3 – “Any Opportunity to Serve” details the twenty years in Franklin’s life when he worked as a printer, and author, and then, towards the end as a natural scientist and inventor. The short version is that the print shop prospered and Franklin got rich. His newspaper sold well, and when he added an annual Almanac, it proved very popular and quite profitable. By 1750, Franklin had invested in other print shops in New York and New Jersey, he was perhaps the largest manufacturer of paper in the British Empire, and he had invested wisely and profitably in real estate. During the 1740s he became the official printer of the colonial government of Pennsylvania. He founded the American Philosophical Society. He was appointed postmaster. He organized the Militia Association and the Union Fire Company. He was also attracted to the preaching of George Whitefield and intrigued by the revival then sweeping the colonies known as the “Great Awakening.” He befriended Whitefield and became his publisher, though he never was personally converted to Christianity. By the end of the decade, at the age of 45, he decided to retire from his business ventures and devote himself to further education, exploration of the natural world, and writing. His investigations and publications on electricity made him famous in Europe as well as the colonies, and he was awarded honorary degrees by both Yale and Harvard. There are four activities for this section: Design and Print an Almanac Cover; Create Charged Cereal; Roll that Can; Fly a Kite.

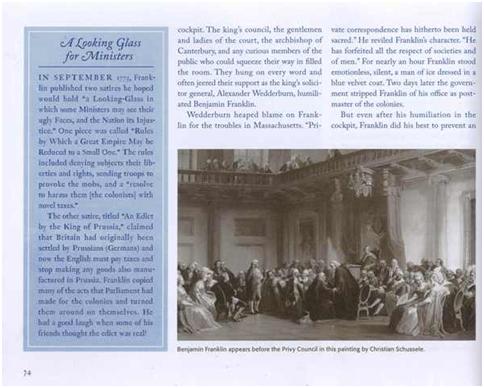

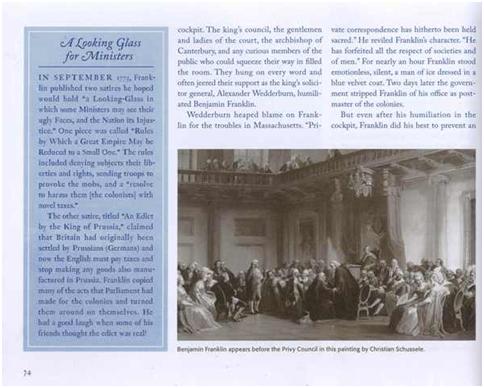

Part 4 – “A Firm Loyalty to the Crown” In the 1750s, Franklin wrote and published dozens of essays, most of them devoted to promoting the development of the American Colonies. He predicted the population would double every twenty years, and that there were many fortunes to be made. He was appointed one of two joint deputy postmasters for all the North American colonies – a task he undertook with energy and enthusiasm. During the French and Indian War, he again organized the colonial militia and was elected Colonel of a 1,000-man regiment. Ben and his eldest son, William, traveled to the frontier and supervised the construction of forts. In 1757, the Pennsylvania legislature sent him to London to negotiate with the Penn family over amendments to the colonial charter. Franklin found himself a celebrity in London – well known from his writings and his experiments with electricity. In 1761, Franklin attended the coronation of George III. After five years in London, Ben returned home to Philadelphia. He stayed only a year, and then was sent back to London a second time to request the King and Parliament end the rule of Pennsylvania by the Penn family. He was to spend the next ten years in London, representing not only Pennsylvania, but eventually being named agent for New Jersey, Georgia, and Massachusetts. He was in London when Parliament passed the Stamp Act, and also when, after violent opposition, they repealed it the next year. He stayed in London through the rest of the decade, and then on into the 1770s. When Boston radicals dumped tea into the harbor rather than pay a tax imposed by Parliament, Franklin was summoned to appear before King George’s privy council and listened for more than an hour while he and the colonists were denounced and insulted. He worked with William Pitt, the Earl of Chatham, to introduce a measure whereby Parliament would voluntarily renounce any authority to impose a tax on the colonies’ internal trade. Pitt’s proposal was rejected. Shortly thereafter, Ben left London and returned to Philadelphia – the city he had left eleven years before. There are two activities for this section: Dig into Your Family Tree; Play a Glass Armonica.

Part 5 – “Snatching the Scepter from Tyrants” When Franklin arrived in Philadelphia, he learned that while he’d been at sea between England and America there had been a battle between the British Regulars occupying Boston and the Massachusetts Militia at Lexington and Concord. A day after his arrival, Franklin was elected as a delegate from Virginia to the Second Continental Congress, which was already meeting in Philadelphia. The next spring, he was appointed to the committee to draft a Declaration of Independence. In the fall, he was commissioned by the Congress to travel to Paris and seek an alliance with the French. In Paris, Franklin found he was a much a celebrity as he had been in London a decade earlier. In 1778, he met Voltaire who proclaimed himself one of Franklin’s admirers. Franklin not only worked towards a formal, open alliance with the French, he also worked quietly on many of the practical needs of the colonial government and the continental army. After Washington forced the surrender of Cornwallis and his army at Yorktown in 1781, Franklin (along with Adams, John Jay, and Henry Laurens) helped to negotiate the treaty with Great Britain which recognized the independence of the colonies. There are three activities for this section: Make Fancy Shoe Buckles; Cook a French Feast; Learn French Words and Phrases.

Part 6 “Something Fit to end With” Ben stayed on in Paris until 1785, when he was succeeded as the United States Ambassador to France by Thomas Jefferson. His sojourn in Europe this time had lasted for nine years. In May of 1787, Pennsylvania sent Franklin as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. At the age of 81, he was the oldest delegate. It was Franklin who nominated George Washington as the presiding officer over the convention. It was Franklin who was instrumental in crafting the compromise between large states and small states that was solved by creating both a Senate and a House of Representatives. After the ratification of the Constitution, Franklin’s last cause was the abolition of slavery. He was already president of the Pennsylvania Society for the Abolition of Slavery. He urged the new Congress of the United States to end slavery, but his appeals were ignored. In April of 1790, at the age of 84, Benjamin Franklin died surrounded by his children and grandchildren. Thus ended a remarkable life which began as a younger son of an English Puritan emigrant to Boston and included a decade of service in London and a decade in Paris. There are four activities for this section: Design a Turkey Seal for the United States; Make a Barometer; Make a Walking Stick for Your Gout; Cast Franklin’s Rising Sun.

Aside from being an excellent biography of Franklin, this book (like all of the Chicago Review Press titles in this series) is unique in its incorporation of practical, hands-on activities for kids. The publisher indicates the text is written for students in grades 3 through 6, and that’s certainly the age range that most of the activities will appeal to – but I suspect that even junior high and high school students will find the biography of Franklin an excellent introduction to his impressive and varied accomplishments.

Ben Franklin: American Genius is a paperback, 128 pages. It is available for $16.95 directly from Greenleaf Press by clicking on any of the links in this review.

– Rob Shearer, Publisher

Other books from Chicago Review Press in this series:

I have just been re-reading The Fellowship of the Ring, and tonight I came to the account of the banquet given by Elrond in Rivendell to celebrate Frodo’s recovery from the knife-wound he suffered at the hand of the Black Riders at weather-top. There is a marvelous description of Elrond seated at the head of the table with Glorfindel seated on his right and Gandalf on his left in places of honor. And under a canopy, Arwen Undomiel. It is achingly beautiful.

I have just been re-reading The Fellowship of the Ring, and tonight I came to the account of the banquet given by Elrond in Rivendell to celebrate Frodo’s recovery from the knife-wound he suffered at the hand of the Black Riders at weather-top. There is a marvelous description of Elrond seated at the head of the table with Glorfindel seated on his right and Gandalf on his left in places of honor. And under a canopy, Arwen Undomiel. It is achingly beautiful.

Sad news reached us today. Another one of the great Eyewitness books from Dorling Kindersley has gone out of print. This time it was Da Vinci and His Times.

Sad news reached us today. Another one of the great Eyewitness books from Dorling Kindersley has gone out of print. This time it was Da Vinci and His Times.

Pilgrim Cat

Pilgrim Cat