No, it’s not a story of a brave young dutch boy… it’s the story of Hans Augusto Reyersbach, a German Jew. He was born in Hamburg in 1898. He loved visiting the zoo with his brother and two sisters. And he loved to draw pictures and paint. And he was good at it. He turned 18 in 1916 and so he joined the German army and fought in Russia. After the war, times were tough in Hamburg. Hans packed up his sketchbooks and paintbrushes and moved to Rio de Janeiro where he managed to make a comfortable living as a commercial artist. While there, he married another German emigre from Hamburg, Margarete.

In 1936, Hans and Margret returned to Europe, and settled in Paris. Margret was a commercial photographer, and her skills complemented Hans’. But their commercial work together wasn’t completely satisfying. They wanted to tell stories. And so, they began writing and drawing illustrations for a children’s book. By 1939, They had several finished stories and several publishers showed interest. In September of that year, World War Two began when the Germans invaded Poland. France and England declared war on Germany, but other than the fighting in Poland, not much happened.

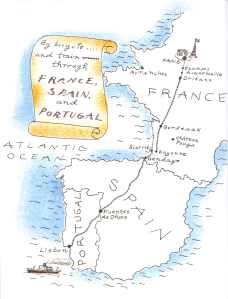

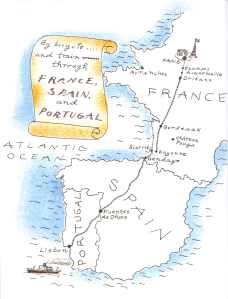

In the spring of 1940, Hans and Margret made a trip to the beaches of Normandy and continued to work on their children’s books. In May, suddenly, things changed. The German army invaded Belgium and the Netherlands and headed for France. Hans and Margret hurried back to Paris and quickly decided they must leave France. They would head first for Brazil (via Portugal), and then perhaps on to the United States. But Paris was in an uproar. By the time Hans had secured the necessary visas, the trains were no longer running from Paris. Hans and Margret didn’t have a car, and besides, the roads were clogged as more than two million Parisians attempted to flee the advancing German armies. Hans managed to find two bicycles, and he and Margret started south. Three days later, they reached Orleans and managed to get on a train headed south. That same day, German troops entered Paris and raised the Nazi flag from the top of the Eiffel Tower.

In the spring of 1940, Hans and Margret made a trip to the beaches of Normandy and continued to work on their children’s books. In May, suddenly, things changed. The German army invaded Belgium and the Netherlands and headed for France. Hans and Margret hurried back to Paris and quickly decided they must leave France. They would head first for Brazil (via Portugal), and then perhaps on to the United States. But Paris was in an uproar. By the time Hans had secured the necessary visas, the trains were no longer running from Paris. Hans and Margret didn’t have a car, and besides, the roads were clogged as more than two million Parisians attempted to flee the advancing German armies. Hans managed to find two bicycles, and he and Margret started south. Three days later, they reached Orleans and managed to get on a train headed south. That same day, German troops entered Paris and raised the Nazi flag from the top of the Eiffel Tower.

Hans and Margret managed to cross the border into Spain on a train headed for Portugal. Because the military dictator of Spain, Franco had been friendly with Germany, they were uneasy until they crossed the border into Portugal three days later. After two weeks frantic travel, they finally made it to Lisbon, Portugal. A month later, they were on a ship for Rio de Janeiro. Two more months of waiting and they managed to get passage on a ship to the United States. October 14, 1940 – four months after they left Paris – they sailed past the Statue of Liberty into New York harbor.

All along the way, Hans had taken great care to make sure that the children’s books they had been working on were kept safe. A year after arriving in New York, Houghton Mifflin published their book. Hans and Margret had titled it The Adventures of Fi-Fi. It was about a monkey and an explorer in a yellow hat who brings him from the jungle to the city. Of course the book needed a new title. Just as Hans and Margret Reyersbach had needed a new name. Reyersbach took too much space on a painting and was too hard for their clients in Rio to remember. And so Hans Reyersbach had taken to signing his artwork as “H.A. Rey.” And their book – well, the editors at Houghton Mifflin had a better name for it, too – Curious George.

And (shamelessly ripping off Paul Harvey), now you know the rest of the story!

The details of the Rey’s amazing escape across wartime France is told in a delightful book published in December, 2005 by Houghton Mifflin, titled: The Journey That Saved Curious George – The True Wartime Escape of Margret and H.A. Rey. Here’s how the publisher describes it:

The details of the Rey’s amazing escape across wartime France is told in a delightful book published in December, 2005 by Houghton Mifflin, titled: The Journey That Saved Curious George – The True Wartime Escape of Margret and H.A. Rey. Here’s how the publisher describes it:

The Journey That Saved Curious George introduces elementary and middle school students to a major event of the twentieth century: World War II. Students will learn about the time period from the many primary sources throughout the book, including photographs, passports, and diary pages.

Louise Borden’s text captures the tension in Paris in 1940 and the urgency to escape, the uprooting of lives, and the difficulty of leaving a place you love. At the same time, this story is about the creative process — the inspiration, joy, and constant work that went into creating the curious, lovable monkey.

Houghton-Mifflin also has an online lesson plan to help teachers use the book.

The book is a 72 pages hardback in full color. The price is $17.00 and it can be ordered directly from Greenleaf Press.

– Rob Shearer

Director, Schaeffer Study Center

Publisher, Greenleaf Press

Overlooked in the debate (at least so far I haven’t seen any citation) has been the quiet, ongoing work of providing military rifles and training to citizens carried out by the Civilian Marksmanship Program for the past 110 years. Recently converted to a congressionally chartered 501(c)(3) corporation, the CMP continues to receive donated .22 and .30 caliber rifles directly from the US Army and provides them at cost to civilians. Before 1996, the CMP was administered directly by the US Army.

Overlooked in the debate (at least so far I haven’t seen any citation) has been the quiet, ongoing work of providing military rifles and training to citizens carried out by the Civilian Marksmanship Program for the past 110 years. Recently converted to a congressionally chartered 501(c)(3) corporation, the CMP continues to receive donated .22 and .30 caliber rifles directly from the US Army and provides them at cost to civilians. Before 1996, the CMP was administered directly by the US Army. The main infantry battle rifle of WW2, the Garand M1 has been available for years, and continues to be sold – including “sniper” models. You can also buy a Garand bayonet.

The main infantry battle rifle of WW2, the Garand M1 has been available for years, and continues to be sold – including “sniper” models. You can also buy a Garand bayonet.

The name that the Scholls chose for their group points to Luther as well. Luther’s symbol or crest, granted him by the Elector of Saxony was

The name that the Scholls chose for their group points to Luther as well. Luther’s symbol or crest, granted him by the Elector of Saxony was  The film had a particular connection to me. When I was 20 years old, I spent a year in Germany as an exchange student. The dormitory I lived in was located on a street called (Siblings Scholl Street).

The film had a particular connection to me. When I was 20 years old, I spent a year in Germany as an exchange student. The dormitory I lived in was located on a street called (Siblings Scholl Street).