Pat Conroy is one of my favorite authors. His writing is lyrical. Some might think it flowery, but that implies soft or overdone. Conroy’s prose is neither. His love for language is evident on every page, in every line. His voice is distinctively male, martial, and Southern. The first book I read by him was The Great Santini: A Novel.

That prompted me to read everything he’s published since. I’ve known the outlines of his personal story – air force pilot father, graduate of the Citadel (South Carolina’s military academy), English teacher, passionate writer.

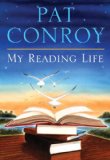

Last fall (Nov 2010), Conroy published a literary memoir, My Reading Life. In fifteen chapters, he describes the books and the teachers who shaped his life. The chapters on his high school and college instructors are a celebration of the power of a gifted teacher to inspire. The chapters on books are breath-taking.

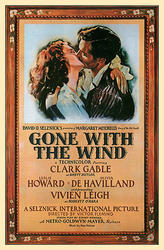

Two chapters impressed me greatly. I was delighted to discover that Gone With the Wind is one of his favorites and shaped him profoundly. It was his mother’s favorite book and she read it out loud to him. I had a similar relationship with both the book and my mother. My mother was old school South. Born in Virginia, she grew up in Atlanta. In 1941, she married her high school sweetheart, my father, who had just graduated from West Point. Gone With the Wind was published in 1936 and won the Pulitzer Prize. The movie was released three years later, in 1939 – the year my mother turned 19. I heard her tell the story of going to downtown Atlanta and joining the crowd at the premiere in order to catch a glimpse of Clark Gable and Vivian Leigh. Pat Conroy’s mother was there, too. Neither could afford a ticket to go in, but they both wanted to be there.

Two chapters impressed me greatly. I was delighted to discover that Gone With the Wind is one of his favorites and shaped him profoundly. It was his mother’s favorite book and she read it out loud to him. I had a similar relationship with both the book and my mother. My mother was old school South. Born in Virginia, she grew up in Atlanta. In 1941, she married her high school sweetheart, my father, who had just graduated from West Point. Gone With the Wind was published in 1936 and won the Pulitzer Prize. The movie was released three years later, in 1939 – the year my mother turned 19. I heard her tell the story of going to downtown Atlanta and joining the crowd at the premiere in order to catch a glimpse of Clark Gable and Vivian Leigh. Pat Conroy’s mother was there, too. Neither could afford a ticket to go in, but they both wanted to be there.

Gone With the Wind was the first “adult” book I can remember reading – when I was 12. I loved the book, and I love the movie. I’ve never really spent much time contemplating why – but after reading Conroy’s descriptions, my immediate reaction was, “I wish I had written that.”

Here is Conroy’s introduction to the book:

“Gone With the Wind is The Iliad with a Southern accent, burning with the humiliation of Reconstruction. It is the song of the fallen, unregenerate Troy, the one sung in a lower key by the women who had to pick up the pieces of a fractured society when their sons and husbands returned with their cause in their throats, when the final battle cry was sounded. It is the story of war told by the women who did not lose it and who refused to believe in its results long after the occupation had begun.”

And here’s his description of Scarlett:

“The book begins and ends with Tara, but it is Scarlett herself who represents the unimaginable changes that the war has wrought on all Southerners. It was in Southern women that the deep hatred the war engendered came to rest for real in the years of Reconstruction. The women of the South became the only American women to know the hard truths of war firsthand. They went hungry just as their men did on the front lines in Virginia and Tennessee, they starved when these men failed to come home for four straight growing seasons, and hunger was an old story when the war finally ended. The men of Chancellorsville, Franklin, and the Wilderness seemed to have left some residue of fury on the smoking, blood-drenched fields of battle, whose very names became sacred in the retelling. But the Southern women, forced to live with that defeat, had to build granaries around the heart to store the poisons that the glands of rage produced during that war and its aftermath. The Civil War still feels personal in the South, and what the women of the South brought to peacetime was Scarlett O’Hara’s sharp memory of exactly what they had lost.”

“The book begins and ends with Tara, but it is Scarlett herself who represents the unimaginable changes that the war has wrought on all Southerners. It was in Southern women that the deep hatred the war engendered came to rest for real in the years of Reconstruction. The women of the South became the only American women to know the hard truths of war firsthand. They went hungry just as their men did on the front lines in Virginia and Tennessee, they starved when these men failed to come home for four straight growing seasons, and hunger was an old story when the war finally ended. The men of Chancellorsville, Franklin, and the Wilderness seemed to have left some residue of fury on the smoking, blood-drenched fields of battle, whose very names became sacred in the retelling. But the Southern women, forced to live with that defeat, had to build granaries around the heart to store the poisons that the glands of rage produced during that war and its aftermath. The Civil War still feels personal in the South, and what the women of the South brought to peacetime was Scarlett O’Hara’s sharp memory of exactly what they had lost.”

“Scarlett springs alive in the first sentence of the book and holds the narrative center for more than a thousand pages. She is a fabulous, one-of-a-kind creation, and she does not utter a dull line in the entire book. She makes her uncontrollable self-centeredness seem like the most charming thing in the world and one feels she would be more than a match for Anna Karenina, Lady Macbeth or any of Tennessee Williams’ women. Her entire nature shines with the joy of being pretty and sought after and frivolous in the first chapters and we see her character darkening slowly throughout the book. She rises to meet challenge after challenge as the war destroys the world she was born into as a daughter of the South. Tara made her charming, but the war made her Scarlett O’Hara.”

“Scarlett springs alive in the first sentence of the book and holds the narrative center for more than a thousand pages. She is a fabulous, one-of-a-kind creation, and she does not utter a dull line in the entire book. She makes her uncontrollable self-centeredness seem like the most charming thing in the world and one feels she would be more than a match for Anna Karenina, Lady Macbeth or any of Tennessee Williams’ women. Her entire nature shines with the joy of being pretty and sought after and frivolous in the first chapters and we see her character darkening slowly throughout the book. She rises to meet challenge after challenge as the war destroys the world she was born into as a daughter of the South. Tara made her charming, but the war made her Scarlett O’Hara.”

Scholars and critics have not cared much for Gone With the Wind. Here is Conroy’s observation on that: “Gone With the Wind has outlived a legion of critics and will bury another whole set of them after this century closes. . . Gone With the Wind has many flaws, but it cannot, even now, be easily put down. It still glows and quivers with life. American letters will always be tiptoeing nervously around that room where Scarlett O’Hara dresses for the party at Twelve Oaks as the War Between the States begins to inch its way toward Tara.”

Thank you, Mr. Conroy, for reminding me about an old friend and for helping me to understand why I love that book and movie.

Here’s a modern version of a trailer for the movie: