a speech given by Rob Shearer at Lipscomb University on Dec 3rd, 2011

part of a Limited Government Seminar sponsored by the Lipscomb University College Republicans

My topic today is the birth of liberty in Europe.

Well, it was born in Europe wasn’t it?

Every generation thinks it was the first to discover sex, so I guess every nation believes it was the one to discover liberty.

I hope to shatter a few illusions this morning. I want to broaden your horizons.

I am going to boldly assert that as young healthy American college students there are a number of things that you believe that aren’t true. Just as a fish never really notices the water, all of us, are usually oblivious to what Emmett Tyrell calls the Kultursmog.

Let me start with three small observations:

- the world did not begin in 1492

- human nature has not changed.

- progress is a myth

The one assertion you can confidently make about human nature over the course of 4,000 years of recorded history is that it has not evolved. In fact, it would be difficult to prove that human nature has appreciably changed.

I would challenge you to read the literature of the ancient world, or the medieval world, or the renaissance or the reformation. If you do, I think you’ll find something surprising. The thoughts, emotions, desires and aspirations of those people will be instantly recognizable and understandable. In truth, they are just like us.

Read the Bible. Read the Hymn to Aton by Pharaoh Akhnaton. Read the Epic of Gilgamesh. Read Homer. Read Augustine . Read Chaucer.

. Read Chaucer.

The people they describe are JUST. LIKE. US.

And they aspired to liberty – individual liberty, political liberty, JUST. LIKE. US.

We didn’t invent the idea of liberty.

It has a long pedigree, with roots back into the ancient world.

And the record of European history, of Western Culture, shows some remarkable periods in which political liberty was achieved.

We are the heirs to that rich European culture.

Our ideas about religion, philosophy, politics, and government have all come to us directly from Europe or through Europe.

But the development of liberty in western culture has followed a long and tortured path. It has not been the steady path of progress. There have been fits and starts. Achievement and decay.

It was anything but inevitable.

Now there is a school of history that believes that the course of history is pre-ordained, and unfolds by inexorable laws. Macaulay, Hegel, Marx and Calvin all have one thing in common. They all believe in predestination.

Calvin… well, let’s leave Calvin out of this. He gets enough grief as it is. I don’t wish to trouble him this morning.

Thomas Babington Macaulay was the great Whig historian of 19th century Britain. For Macaulay, all of recorded human history was simply documentation of the unfolding idea of freedom which came to its fulfillment in that best of all possible representative constitutional, representative governments – 19th century Britain.

Thomas Babington Macaulay was the great Whig historian of 19th century Britain. For Macaulay, all of recorded human history was simply documentation of the unfolding idea of freedom which came to its fulfillment in that best of all possible representative constitutional, representative governments – 19th century Britain.

Hegel is the great German philosopher of the 19th century. For Helgel, all of recorded human history was simply the record of the unfolding and developing idea of freedom, which, by way of the dialectic, revealed itself in ever more refined and perfect fashion until it reached its culmination in 19th century Germany.

Hegel is the great German philosopher of the 19th century. For Helgel, all of recorded human history was simply the record of the unfolding and developing idea of freedom, which, by way of the dialectic, revealed itself in ever more refined and perfect fashion until it reached its culmination in 19th century Germany.

Marx believed that all of recorded human history is simply the clash of economic classes and forces and that the course of history was certain and determined and would inevitably lead to the overthrow of each imperfect intermediate form of government until history was fulfilled in the workers’ paradise of a true communist state where the private ownership of capital would be abolished, and rule by the dictatorship of the proletariat. He thought that this would inevitably happen first in the most industrialized nations of the 19th century: either Britain, Germany, or the United States. Such a revolution, of course, could never occur in the less developed more rural nations on the edge of Europe or outside of European civilization. Certainly never in a country as backward and agricultural as Russia (where they still had serfs when Das Kapital was written!)

Marx believed that all of recorded human history is simply the clash of economic classes and forces and that the course of history was certain and determined and would inevitably lead to the overthrow of each imperfect intermediate form of government until history was fulfilled in the workers’ paradise of a true communist state where the private ownership of capital would be abolished, and rule by the dictatorship of the proletariat. He thought that this would inevitably happen first in the most industrialized nations of the 19th century: either Britain, Germany, or the United States. Such a revolution, of course, could never occur in the less developed more rural nations on the edge of Europe or outside of European civilization. Certainly never in a country as backward and agricultural as Russia (where they still had serfs when Das Kapital was written!)

We laugh at the naiveté of these historians now… and think them parochial for advancing their own nations as the high point of history.

And then, of course, we’re guilty of the same thing.

We order the past to show how several thousand years of history were but prologue to the inevitable and pre-ordained emergence of the American republic.

This notion of history (quite widely and popularly held) is why many of the American historians of my generation have gone out of their way to attack the virtues of the founders.

The truth is, the founding of the American Republic is a remarkable and rare event in history.

Let me reassure you that I admire and revere the founders of the United States. I believe that Washington, Adams, Jefferson, & Franklin were remarkable and praiseworthy men.

Let me reassure you that I admire and revere the founders of the United States. I believe that Washington, Adams, Jefferson, & Franklin were remarkable and praiseworthy men.

But I want to suggest to you this morning that the founding of the American Republic was not as original as we sometimes think… nor was it inevitable.

So let me go back to the western European history and highlight places where Liberty appears.

But first, let me point out that Liberty & Law are inextricably intertwined.

Liberty is not license or lawlessness.

In fact, there can be no liberty without a recognized body of law (Hobbes & Locke had much to say about this, but let me come back to them later.)

Liberty depends upon a shared, recognizable concept of law – natural law.

Liberty and natural law are intertwined.

The notion that there is a natural moral law that is intrinsic, built-in to the universe, and discoverable is an idea with a long pedigree. It was something the Jews, the Greeks, and the Romans all agreed upon. They might have disagreed with each other over who was the author of this law, or over some of the particulars, but they all agreed and acknowledged that natural law was an objective fact.

The birth and expansion of liberty has deep roots. It is a long tale.

Now of course, modern Europeans have abandoned the idea of natural law – just as they have abandoned the notion of objective truth. This doesn’t mean that either have ceased to exist – only that the Europeans have ceased believing in them.

But a belief in natural law and a devotion to discovering, or at least outlining, its details is a central part of the story of liberty in western culture.

But natural law by itself does not generate personal liberty, or political liberty.

Personal, political liberty depends upon the notion that natural law limits the actions of everyone in society.

Tyranny, despotism, oligarchy, aristocracy all are antithetical to liberty, because they all believe that there are some people who are not obligated to obey natural law.

Liberty is achieved to the extent that the wealthy, the privileged, the aristocrats, the king and his officers are all forced to obey, equally the natural law.

So long as there are some people who are above the law, liberty is curtailed.

When all are equal before the law, there is liberty.

THAT idea as you might imagine took a long time to succeed.

To achieve liberty, you must limit government. You must limit the king. You must limit the kings officers.

And they’d rather NOT be limited or held accountable, thank you very much – so they resist.

The struggle to achieve liberty then is a struggle to limit government – not to throw off the natural law, but to bring everyone under the law.

Let me outline for you briefly some highlights in the history of the struggle to achieve liberty – the struggle to limit government

It is useful to remind us how costly the struggle has been, how much patience and perseverance it has taken to guard the spark and flame over long centuries, and how irregular the course was. The many setbacks are a useful reminder to us that the unfolding of liberty was anything but inevitable.

In the ancient world, you can do no better than to make a comparative study of the political history of Israel, Greece, and Rome – coincidentally, the three streams of political thought & philosophy which lie at the heart of western European culture.

And in all three you find a curious sequence of events. The unfolding of liberty is not a linear tale of progress. Israel is ruled by Patriarchs & Judges, then by Kings. The kings (as prophesied) are more oppressive in their rule than were the judges, and to make matters worse the Kings, over time get progressively worse, not better! In fact you could argue that a graph of the political history of Israel has a downward slope – the opposite of progress.

And in all three you find a curious sequence of events. The unfolding of liberty is not a linear tale of progress. Israel is ruled by Patriarchs & Judges, then by Kings. The kings (as prophesied) are more oppressive in their rule than were the judges, and to make matters worse the Kings, over time get progressively worse, not better! In fact you could argue that a graph of the political history of Israel has a downward slope – the opposite of progress.

Hmmm…

Well, let us turn to Greece. The political history of the Greek city states is rich and varied. And the Greeks give us the democracies of the city-states like Athens, Corinth, and… Sparta? Wait. How many of you saw The 300? The Spartans represent a strand of Greek culture that values honor and the battle-skills of well-trained soldiers far above liberty. And over time, which strand of Greek culture came to dominate. Did the Greek city states gradually merge into a larger, representative political union? No, in fact the Greek city states either succumbed to their own demagogues and tyrants, or in the end they were conquered by Alexander and his Macedonian phalanxes, and came under what can only be described as a military dictatorship.

Well, let us turn to Greece. The political history of the Greek city states is rich and varied. And the Greeks give us the democracies of the city-states like Athens, Corinth, and… Sparta? Wait. How many of you saw The 300? The Spartans represent a strand of Greek culture that values honor and the battle-skills of well-trained soldiers far above liberty. And over time, which strand of Greek culture came to dominate. Did the Greek city states gradually merge into a larger, representative political union? No, in fact the Greek city states either succumbed to their own demagogues and tyrants, or in the end they were conquered by Alexander and his Macedonian phalanxes, and came under what can only be described as a military dictatorship.

How would you graph liberty over the history of ancient Greece?

And now, let us turn to Rome.

The Romans achieved remarkable stability in their government and successfully pacified and governed the entire Mediterranean world – the pax romana. And Rome was a republic. The republic held elections for the office of consul every year. And the Roman republic achieved political stability by dividing political authority – not just between two co-equal consuls, but between consuls and senators and a host of other prominent officials.

The Romans achieved remarkable stability in their government and successfully pacified and governed the entire Mediterranean world – the pax romana. And Rome was a republic. The republic held elections for the office of consul every year. And the Roman republic achieved political stability by dividing political authority – not just between two co-equal consuls, but between consuls and senators and a host of other prominent officials.

But what happened to Rome? How do we explain/ what answer do we give to Gibbon’s great historical work titled The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire? (published in 1776, by the way – this is called foreshadowing)?

Actually, I think Gibbon’s work asks the wrong question. It’s not really even all that very interesting a question. He thought the answer was that Christianity had undermined the old Roman virtues and weakened Rome. I think that’s a preposterous answer by the way. But Gibbon work asks the wrong question.

The much more interesting, much more important question is “Why did the Roman Republic fail?” Not the Empire, the REPUBLIC! Why did Rome cease being a Republic and become an Empire.

The peak of Roman civilization is during the days of the Republic. When the Republic fails and Rome becomes an Empire it is a sign that things have already gone badly wrong. The Roman Emperors were not nice men. That fact is masked for us, because in the movies they always speak with British accents and seem refined and cultured. But they were not nice men. Almost every single one of them was a general and owed his title to the backing of the army. The ugly truth (seldom spoken) is that the Roman Empire was a military dictatorship. And like many military dictatorships, the most frequent method of regime change was a military coup. Roman Empire is a misnomer. It was not so much the Roman Empire as it was the Roman Banana Republic – 500 years of military dictatorship.

The peak of Roman civilization is during the days of the Republic. When the Republic fails and Rome becomes an Empire it is a sign that things have already gone badly wrong. The Roman Emperors were not nice men. That fact is masked for us, because in the movies they always speak with British accents and seem refined and cultured. But they were not nice men. Almost every single one of them was a general and owed his title to the backing of the army. The ugly truth (seldom spoken) is that the Roman Empire was a military dictatorship. And like many military dictatorships, the most frequent method of regime change was a military coup. Roman Empire is a misnomer. It was not so much the Roman Empire as it was the Roman Banana Republic – 500 years of military dictatorship.

So the real, important question to be asked of Roman history is not why did the Empire fall, It’s why did the Republic fall? Why did it cease to hold elections and turn into a military dictatorship?

I challenge you to take up the study of Roman history. The answer to that question is fascinating, and frightening.

I could say much about the Middle Ages and the Germanic kingdoms that succeeded Rome. Here again, our nomenclature is misleading. Rome was not conquered by the Germanic tribes. The Germanic tribes had no kingdoms of their own. They were homeless. They crossed the frontier of Rome (the Danube River) as illegal immigrants. And the hollow and rotted out shell of the Roman Empire collapsed under the weight of their migrations.

And in one of the great ironies of church history, barely a century after the urban, lower-class persecuted Christian church had succeeded in converting the Roman aristocracy, Rome was conquered by pagan barbarian tribes and it would take several more centuries for the conquered Roman Christians to convert their Barbarian masters.

Much could and should be said about the development of law and liberty in medieval and renaissance Europe. The struggles of the 12th & 13th century led to The Great Charter of the Liberties of England, and of the Liberties of the Forest – a radical notion that the king was bound by the law.

That notion was more prominent in the late Middle Ages and then was rejected by the monarchs of the 16th & 17th centuries who claimed to rule by direct authority from God. England went through a civil war and ten years of military dictatorship sorting that out. The result brought the king’s back under the authority of the Magna Charta and the law. One could argue that Locke, Hobbes, and the Glorious Revolution were a recovery and revival of early medieval notions of kingship.

But I want to come back to that bit of foreshadowing I spoke of before. I don’t want to steal the thunder of the next figure, but I want to make an important point about the connection between liberty in the United States and liberty in Europe.

I mentioned that Gibbon published The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire in 1776. His work typified the ongoing study of the ancient world which had been revived in Europe at the end of the middle ages.

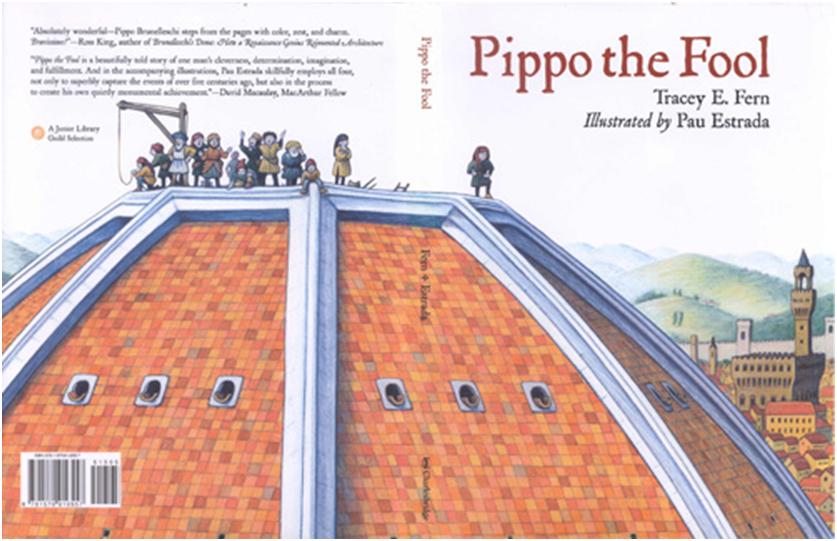

At the end of the Middle Ages came a period of time dubbed the renaissance or rebirth because of a widespread movement which sought to revive the ancient world. Across European culture, for several centuries, there was an intense interest and devotion to studying Greece and Rome. It began with a revival of languages and literature. It spread to a revival of artistic styles and subjects. The protestant Reformation itself fits organically into this cultural preoccupation with reviving the classical world. This fascination with the ancient world persisted for several centuries. It was the exact opposite of our modern notion of progress. Renaissance men did not believe that everyone who had lived before them was stupid and insignificant. Rather, they believed that the wisdom of the ancient world had been tragically lost and that it could and should be rescued and revived. The motto of the Renaissance was “ ad fonts” – back to the sources.

The culture of the 18th century, the 1700s in America was still the culture of the Renaissance, with an emphasis on studying the classics of Greece & Rome. The culture of the Enlightenment and the rejection of authority and the past was just developing in Europe – but not yet in North America. The colonies were not on the cutting edge of cultural trends. They were a cultural backwater, lagging behind and maintaining the attitudes and culture of earlier centuries.

And what model did the American colonists turn to when they wished to establish a new form of government, independent of the British monarchy? They consciously chose the form and features of the Roman Republic – with an eye towards avoiding its deficiencies, but with a thoughtful recognition that it had governed the Roman World successfully for 500 years.

And so I would assert that the founding of the Roman Republic is the last expression and accomplishment of the spirit of the Renaissance. It looks backwards to the ancient world for guidance and wisdom. The renaissance began with language and literature and spread to the arts. The spirit of the renaissance, when applied to the problems of the church produced the upheavals of the protestant reformation.

And then finally, the renaissance results in the revival of ancient political thought and forms and the founding of the American republic.

The American revolution looks back to the ancient world. The French revolution is a horse of a different color. Its spirit is almost the antithesis of the renaissance. It rejects all past authority. It treats all ancient authority with suspicion and contempt. The proximity in time is misleading. They not the expressions of the same cultural movement, they are the antithetical expressions of two separate and opposite cultural movements.

So. The origin of Liberty in Europe took us back to ancient Rome, via the Renaissance.

And the cautionary part of that tale is that each expression of liberty which I have mentioned was not marked by a slow, steady progressive improvement. Rather in Israel, in Greece, in Rome, in the Middle Ages there are brief, compressed, miraculous expressions and instantiations of Liberty. But they do not last. They decay, they decline, they rot. Sometimes quickly, sometimes slowy. But they do not build upon each other brick on brick, course on course.

The course rather is a sawtooth pattern. Liberty is achieved… and then begins to fade, and often seems to disappear – until another generation comes along and is miraculously empowered to create a culture, a movement, a political nation where liberty becomes real.

May your generation be such a miraculously empowered generation. Because we do not need progress. We need a renaissance of liberty. We need a revival of liberty.

Thank you.

Steven Ozment is, undoubtedly, one of the leading historians of the Reformation in the world. I first read his early, seminal works in grad school (The Reformation in the Cities and The Age of Reform 1250-1550). He is a professor of history at Harvard where he continues to teach both graduate students and undergraduate course in western civilization.

Having said all that, there is one howler in Ozment’s otherwise astute analysis that is indicative of one of the blind spots of current historical analysis.

Having said all that, there is one howler in Ozment’s otherwise astute analysis that is indicative of one of the blind spots of current historical analysis.