John Taylor Gatto has a new book out. That is cause for celebration. For those who are not familiar with him, a bit of his biography is in order. Gatto taught for 30 years in the public schools of New York City, specifically Community School District 3, Manhattan. He was named New York City Teacher of the year in 1989, 1990, and 1991, and New York State Teacher of the Year in 1991. In 1991 he quit his teaching job rather publicly, with an editorial in the Wall Street Journal which began thus:

John Taylor Gatto has a new book out. That is cause for celebration. For those who are not familiar with him, a bit of his biography is in order. Gatto taught for 30 years in the public schools of New York City, specifically Community School District 3, Manhattan. He was named New York City Teacher of the year in 1989, 1990, and 1991, and New York State Teacher of the Year in 1991. In 1991 he quit his teaching job rather publicly, with an editorial in the Wall Street Journal which began thus:

Government schooling is the most radical adventure in history. It kills the family by monopolizing the best times of childhood and by teaching disrespect for home and parents.

You can read the rest of his provocative essay / editorial / resignation letter at his website: http://www.johntaylorgatto.com/underground/prologue2.htm

In 1992, Gatto published a revolutionary book, Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling. Seventeen years later, that book is still in print. Since 1992, he has been writing and speaking nationwide. Among other things he has been outspoken in his admiration for the modern homeschooling movement – though he didn’t homeschool his own children.

In 1992, Gatto published a revolutionary book, Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling. Seventeen years later, that book is still in print. Since 1992, he has been writing and speaking nationwide. Among other things he has been outspoken in his admiration for the modern homeschooling movement – though he didn’t homeschool his own children.

In 2001 he published The Underground History of American Education . Extensively researched, the book is, in some ways, Gatto’s magnum opus. In it, he documents in detail the movement begun in the late 19th century to adopt the Prussian model of compulsory schooling in order to train docile factory workers and obedient soldiers. It is an eye-opening study. It can be ordered from Amazon, or read online at Gatto’s website.

. Extensively researched, the book is, in some ways, Gatto’s magnum opus. In it, he documents in detail the movement begun in the late 19th century to adopt the Prussian model of compulsory schooling in order to train docile factory workers and obedient soldiers. It is an eye-opening study. It can be ordered from Amazon, or read online at Gatto’s website.

And now we have his newest composition. In some important ways, I think it may be his best work. Many of the themes of his writing are repeated here, but they are more polished, more concise, more persuasively presented. And there are some provocative and startling new ideas here as well. Ideas that will (or should) make anyone involved in the education of children think.

The dedication opens poignantly:

I dedicate this book to the great and difficult art of family-building, and to its artists, the homeschoolers in particular . . .

From Gatto’s Prologue: Against School:

Do we really need school? I don’t mean education, just forced schooling: six classes a day, five days a week, nine months a year, for twelve years. Is this deadly routine really necessary? And if so, for what? Don’t hide behind reading, writing, and arithmetic as a rationale, because 2 million happy homeschoolers have surly put that banal justification to rest.

A little later, Gatto quotes H.L. Mencken with approval:

The aim of public education is not to fill the young of the species with knowledge and awaken their intelligence. . . Nothing could be further from the truth. The aim. . . is simply to reduce as many individuals as possible to the same safe level, to breed and train a standardized citizenry, to put down dissent and originality. That is its aim in the United States. . . and that is its aim everywhere else.

In chapter one (Everything You Know about Schools is Wrong) Gatto summarizes the startling and alarming statistics on literacy, gathered from a large and impeccable source, US Army induction records. In the early 1930s, the literacy rate for young men was 98%. By 1944, it was 96%. But by 1951 it had fallen to 81% – a startling decline. By 1973, the tests on young men inducted into the military revealed that male literacy had fallen to 73%. All of this in spite of the increased attention in the 1950s and 1960s on education. Spending on education had skyrocketed. New teachers had been trained and hired. New methods had been developed and adopted. What went wrong? Gatto suggests that education was never the stated purpose of compulsory schooling – control and conditioning was. He has quotes from the founding documents of public schooling to back up his assertions.

In chapter two (Walkabout: London), Gatto celebrates the lives of successful men and women who have achieved remarkable things without formal “schooling” (which doesn’t mean they weren’t educated!). Sir Richard Branson, David Sarnoff, & Bill Gates are 3 of his more important examples but there are others with life-stories every bit as compelling.

In chapters three & four (Fat Stanley and the Lancaster Amish & David Sarnoff’s Classroom), Gatto continues his examples and contrasts those who have learned how to think with the stunting effects of twelve years of classroom confinement.

Chapter five (Hector Isn’t the Problem) tells the tragic story of a student with behavior problems who is labeled and kept in school’s version of “protective custody. In Chapter six (The Camino de Santiago) Gatto begins to lay out one of the guerilla techniques he developed to help his students really learn – by helping them to escape the artificial setting of the classroom and observe the real world. Chapter seven (Weapons of Mass Instruction) expands on this theme and gives more examples of what Gatto discovered really helps students and how schooling systematically stifles them.

Chapter eight, (What is Education?) is a thought experiment in which Gatto imagines what the goals and methods of a new school, a humane school would look like. No testing, flexible time commitments, no walled compound:

I know how odd this all sounds: first I tell you reading, writing, and arithmetic are easy to learn as long as they aren’t taught systematically, and now I tell you that the very “comprehensive” school institution which Harvard called for in the 1950s is ruining our children, not helping them. I know you’ve been told by experts that the complicated world of today requires more school time, longer school days, longer years, more testing, more labeling.

Well. . . you’ve been bamboozled, and I hope your own experience will confirm that by little reflection. How do you think millions of Americans learned to be literate on desktop computers, and all the rest of the paraphernalia of the information society? Not at school, that’s for sure.

Chapter 9 is a personal plea from Gatto entitled, “A Letter to My Granddaughter About Dartmouth.” In it, he advises her to take a few years off and work until she understands herself better. And then he gives her a frank appraisal of what she will, and won’t, learn at Dartmouth.

Chapter 10 (Incident at Highland High) was my favorite chapter in the book! Gatto relates two incidents. The first was the 2008 incident in Germany in which a sixteen-year-old girl was forcibly removed from her home by a group of fifteen policemen and city officials. Her crime – she was being homeschooled and did not want to attend the local public schools. Gatto reprints the letter he wrote to the German ambassador in the US. He also relates his own experience in dealing with official repression and over-reaction. In 2004, while giving a talk to the students at Highland High School in Rockland County, NY he was interrupted by three police officers who burst into the auditorium and announced (via bull-horn) that the assembly was over and all students were to return to their classrooms. The superintendent of schools had found Gatto’s talk to be so inflammatory that he called the police to stop it.

In his Afterword, Gatto announces, An Invitation to an Open Conspiracy: The Bartleby Project. Inspired by Herman Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener, a boycott of standardized testing:

Mass abstract testing, anonymously scored, is the torture centrifuge whirling away precious resources of time and money from productive use and routing it into the hands of testing magicians. It happens only because the tormented allow it. Here is the divide-and-conquer mechanism par excellence, the wizard-wand which establishes a bogus rank order among the schooled, inflicts prodigies of stress upon the unwary, causes suicides, family breakups, and grossly perverts the learning process – while producing no information of any genuine worth. Testing can’t predict who will become the best surgeon, college professor, or taxicab driver; it predicts nothing which would impel any sane human being to enquire after these scores. Standardized testing is very good evidence our national leadership is bankrupt and has been so for a very long time.

His solution? When the tests are handed out on test day, Gatto urges young people to write across the front of the test, “I would prefer not to take your test.” And don’t. “An old man’s prayers will be with you.”

Weapons of Mass Instruction is a hardback, 215 pages. It can be purchased directly from Greenleaf Press for $24.95 by clicking on any of the links in this review.

– Rob Shearer

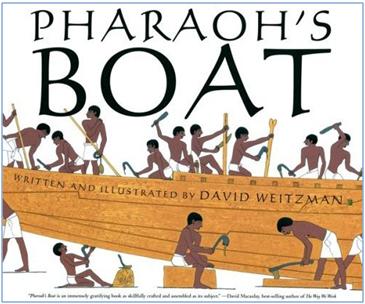

The importance of understanding Egyptian history and culture can hardly be over-estimated. Egypt is the country mentioned most often in the Old Testament. Israel’s prophets foretell the future not just for Israel, but for Egypt as well.

The importance of understanding Egyptian history and culture can hardly be over-estimated. Egypt is the country mentioned most often in the Old Testament. Israel’s prophets foretell the future not just for Israel, but for Egypt as well.

To tell the story of their discovery and re-assembly, Weitzman switches to a more modern 3-dimensional representational style. The story of the painstaking research that went into re-assembling the boat is as fascinating as the story of their original construction. It was a 3-dimensional jigsaw puzzle with 1,200+ pieces, and no pictures or instructions. Before the Egyptian archeologist, Ahmed Youssef Moustafa, chief of the Restoration Department of the Egyptian Antiquities Service was satisfied, the boat had been put together and taken apart five times. Each time, the team of archeologists learned something new. To solve several particularly difficult problems, Ahmed went to modern Egyptian boat-makers on the banks of the Nile and served as an apprentice, asking questions about the details of the techniques they used. It turns out that many things have stayed the same for over 4,000 years.

To tell the story of their discovery and re-assembly, Weitzman switches to a more modern 3-dimensional representational style. The story of the painstaking research that went into re-assembling the boat is as fascinating as the story of their original construction. It was a 3-dimensional jigsaw puzzle with 1,200+ pieces, and no pictures or instructions. Before the Egyptian archeologist, Ahmed Youssef Moustafa, chief of the Restoration Department of the Egyptian Antiquities Service was satisfied, the boat had been put together and taken apart five times. Each time, the team of archeologists learned something new. To solve several particularly difficult problems, Ahmed went to modern Egyptian boat-makers on the banks of the Nile and served as an apprentice, asking questions about the details of the techniques they used. It turns out that many things have stayed the same for over 4,000 years.